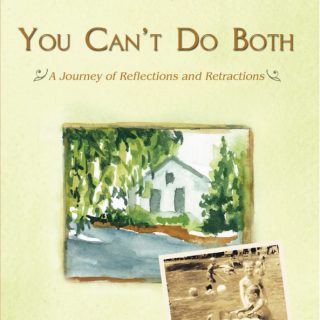

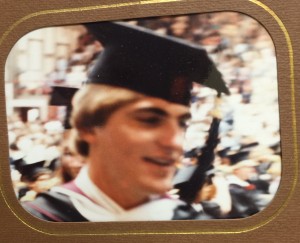

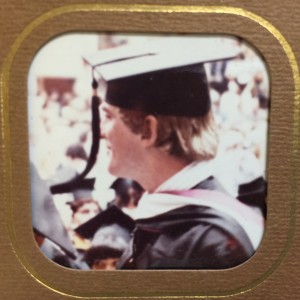

The hard rain was unrelenting. It was that close to twilight time on a Sunday evening that no matter who you are with, you feel alone. The traditional day of rest presents an opportunity to look ahead and reflect on what you have left behind. I am the sole passenger in my car, a solitary silhouette behind the steering wheel. All I have is my music and my thoughts as I follow the dark Nissan Maxima that is in front of me. Through the downpour , I am comforted only by the red taillights from the car in my lead, carrying some friends, as we make our way toward New York from Pennsylvania. Only three hours earlier my parents, and my second mom, Sue Dorado were the lone representatives for me at the Muhlenberg College graduation of 1982. As I listened to Supertramp with their insistence for me to “take the long way home”, I was confused as to where exactly “home” was anymore. My undergraduate days in Allentown were over and with the depressed outlook for Bethlehem Steel my aspirations of starting a career in teaching would not, and could not happen in Allentown. The area’s steady economic decline was punctuated by not one teaching hire in the Lehigh Valley in the last five years. My wipers were going at full tilt clearing the water from my windshield but they could do nothing about the mist surrounding my eyes. I had shown up as a scared Muhlenberg freshman–immature, and lonely– in my grandmother’s old blue convertible. Four years later degree in hand , I drove off campus in the same car, but I was somebody completely different.

The hard rain was unrelenting. It was that close to twilight time on a Sunday evening that no matter who you are with, you feel alone. The traditional day of rest presents an opportunity to look ahead and reflect on what you have left behind. I am the sole passenger in my car, a solitary silhouette behind the steering wheel. All I have is my music and my thoughts as I follow the dark Nissan Maxima that is in front of me. Through the downpour , I am comforted only by the red taillights from the car in my lead, carrying some friends, as we make our way toward New York from Pennsylvania. Only three hours earlier my parents, and my second mom, Sue Dorado were the lone representatives for me at the Muhlenberg College graduation of 1982. As I listened to Supertramp with their insistence for me to “take the long way home”, I was confused as to where exactly “home” was anymore. My undergraduate days in Allentown were over and with the depressed outlook for Bethlehem Steel my aspirations of starting a career in teaching would not, and could not happen in Allentown. The area’s steady economic decline was punctuated by not one teaching hire in the Lehigh Valley in the last five years. My wipers were going at full tilt clearing the water from my windshield but they could do nothing about the mist surrounding my eyes. I had shown up as a scared Muhlenberg freshman–immature, and lonely– in my grandmother’s old blue convertible. Four years later degree in hand , I drove off campus in the same car, but I was somebody completely different.

As people grow older, their college experience becomes more nostalgic and seemingly more magical. For many, their days as a collegian are described as the best days of their lives. Statistics say that 28% of married people met their spouses while attending college together. Also, close to 50% of young adults who go far away for their formal education end up getting a job and locating near where they did their undergraduate work. Not necessarily by choice it turned out for me that I did not marry a girl who attended Muhlenberg with me, nor did I stay in the Allentown area. This is not to downplay the impact my four years in central Pennsylvania had on me. The local vernacular still resonates. I would make a statement:

As people grow older, their college experience becomes more nostalgic and seemingly more magical. For many, their days as a collegian are described as the best days of their lives. Statistics say that 28% of married people met their spouses while attending college together. Also, close to 50% of young adults who go far away for their formal education end up getting a job and locating near where they did their undergraduate work. Not necessarily by choice it turned out for me that I did not marry a girl who attended Muhlenberg with me, nor did I stay in the Allentown area. This is not to downplay the impact my four years in central Pennsylvania had on me. The local vernacular still resonates. I would make a statement:

“ I got a B- on my Comparative Religion test.”

The Allentown linguistic reply: “Did you, now?”

Subs became hoagies, Philly cheese steaks replaced pizza as my favorite meal, and rolling rock started to taste better than Pabst Blue Ribbon. It was hard to determine who I loathed more the Phillies, Flyers, 76ers, or Eagles. To make matters worse they all had very good teams in the years I attended Muhlenberg. The larger impact for me had to do with the lessons that, over four years, changed who I thought I had been, who I was in the present…. and who I wanted to become.

Subs became hoagies, Philly cheese steaks replaced pizza as my favorite meal, and rolling rock started to taste better than Pabst Blue Ribbon. It was hard to determine who I loathed more the Phillies, Flyers, 76ers, or Eagles. To make matters worse they all had very good teams in the years I attended Muhlenberg. The larger impact for me had to do with the lessons that, over four years, changed who I thought I had been, who I was in the present…. and who I wanted to become.

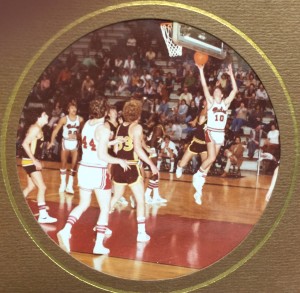

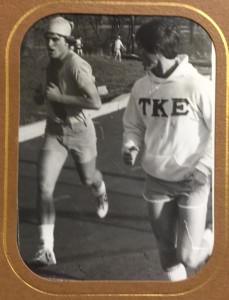

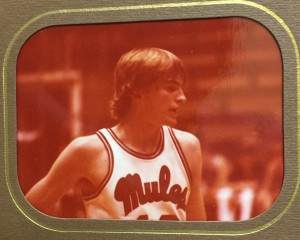

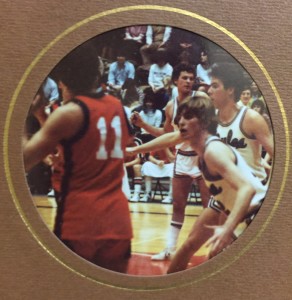

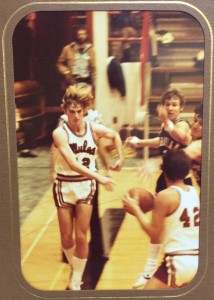

When I look back on my days at Muhlenberg , the constants of my memory’s visions are pledging a fraternity and my experiences on the basketball team. Those images find their way into my dreams even today. The vulnerability I felt from the competition, and attempts to define myself reverberate through my body still. But it was in the classroom, although not as obviously, I found the beginnings of a person who had not been but was to be. Of all the venues in my young life, the classroom had always left me feeling the most inadequate. At Muhlenberg I was surrounded by an exuberant amount of nerdy, but cut-throat future physicians. I was in class with people where getting A’s was a matter of life or death. The liberal arts program required credits in Intermediate Language, Religion, History, English, Math, and Science.

When I look back on my days at Muhlenberg , the constants of my memory’s visions are pledging a fraternity and my experiences on the basketball team. Those images find their way into my dreams even today. The vulnerability I felt from the competition, and attempts to define myself reverberate through my body still. But it was in the classroom, although not as obviously, I found the beginnings of a person who had not been but was to be. Of all the venues in my young life, the classroom had always left me feeling the most inadequate. At Muhlenberg I was surrounded by an exuberant amount of nerdy, but cut-throat future physicians. I was in class with people where getting A’s was a matter of life or death. The liberal arts program required credits in Intermediate Language, Religion, History, English, Math, and Science.  I was nothing more than a cocky bull-shitter. I was okay in any class where there weren’t pre-defined answers required. I had quit on math when letters were thrown in with numbers on the blackboard, and the only thing I knew about science was that half the day was light and the other half dark. But somewhere I found the motivation to do what it took to get through the curriculum. I went to class, took notes, studied and actually read a couple of books. My efforts got me a pile of B’s and C’s. My college transcript would confirm that with the exception of when I did my student teaching I received one A in my four years at Muhlenberg . That was in the very non-scientific or mathematical Bullshitting Class, or as it read on my course schedule , Public Speaking.

I was nothing more than a cocky bull-shitter. I was okay in any class where there weren’t pre-defined answers required. I had quit on math when letters were thrown in with numbers on the blackboard, and the only thing I knew about science was that half the day was light and the other half dark. But somewhere I found the motivation to do what it took to get through the curriculum. I went to class, took notes, studied and actually read a couple of books. My efforts got me a pile of B’s and C’s. My college transcript would confirm that with the exception of when I did my student teaching I received one A in my four years at Muhlenberg . That was in the very non-scientific or mathematical Bullshitting Class, or as it read on my course schedule , Public Speaking.

Even though it was mid-February, the radio stations in Allentown were already hyping Phillies baseball. It was the first day of spring training and it was also my first day of student teaching at Dieruff High School, one of two high schools located in Allentown. I had come to Muhlenberg as a communications major, fell in love with history in Ed Baldridge’s class, and somewhere in my junior year decided I wanted to teach and coach. I got out of the car on that winter morning and I could feel an assortment of teenage eyes on me. The attention and recognition of being put on a pedastil by my new students was my new drug that would turn out to be a hard habit to break.

Even though it was mid-February, the radio stations in Allentown were already hyping Phillies baseball. It was the first day of spring training and it was also my first day of student teaching at Dieruff High School, one of two high schools located in Allentown. I had come to Muhlenberg as a communications major, fell in love with history in Ed Baldridge’s class, and somewhere in my junior year decided I wanted to teach and coach. I got out of the car on that winter morning and I could feel an assortment of teenage eyes on me. The attention and recognition of being put on a pedastil by my new students was my new drug that would turn out to be a hard habit to break.

For a football coach Larry Lewis was a little man. It was unusual for the head football coach of a large city high school to teach any classes that involved actual teaching, but Coach Lewis taught five classes of advanced American History.

“Hi Rich, I heard a lot about you. They tell me you don’t need much rehearsal, that you are ready for prime time.”

“Hi Rich, I heard a lot about you. They tell me you don’t need much rehearsal, that you are ready for prime time.”

I don’t remember responding. “This is what page we are on, all five preps are the same, and here is the attendance and grade book. In an emergency I will be in the coach’s office.”

So that was it… my career as a teacher was taking flight and I was on my way to my second A. My student teaching experience was the first time in my life that I found my voice. I felt a true sense of value and esteem that was so different than scoring points on the basketball court or anywhere else.

While I spent the second semester of my senior year looking for a way of life, the first semester was spent looking for the party. By the time it had reached the fall of my Senior year, I was feeling my oats. I am a fashionably late type of person when it comes to everything, but now I was ready to step out. Our five man suite was to be occupied by three TKE brothers (Myself, Tom Wagner, and Kurt Jack), two of them on the Varsity basketball team and two Phi Tau brothers (Steve Digregorio, and Ozzie Breiner) both linemen on 1980 Championship Muhlenberg football team. It was only a couple weeks before school started that Wags’ dad passed away, forcing him to live at home for his senior year. That left a little nerdy freshman, Brad Moore, who now goes by the more distinguished Brad Moore M.D., stuck in an apartment with four self-appointed BMOC’s (Big Men on Campus). The person in charge of housing at Muhlenberg who did that to poor Brad should have been fired immediately.

Brad would claim later that in general terms he found the four of our lifestyles shocking. But his eyes opened the widest by the activities of the 22-year-old senior who lived in the single. To his three other suite mates, Brad would make inquiries into the mysterious enigma that was me.

Brad would claim later that in general terms he found the four of our lifestyles shocking. But his eyes opened the widest by the activities of the 22-year-old senior who lived in the single. To his three other suite mates, Brad would make inquiries into the mysterious enigma that was me.

“Do you think we should tell the campus police about Rich? Does he have any classes? Why do I see people coming and going from his room but never him?”

Ozzie and Steve would tell me some of the questions Brad would pose to them. My two roomies would answer with “Wait til the weather warms up, we will see a little more of him then,” and “he has a lot of important unspeakable business to do.”

The dichotomy of Brad and I was more perception than reality. Somewhere in the space of that year we grew to have an affection for each other. The nerdy freshman and the self-absorbed senior had more in common than either one could have ever imagined.

The two cars were still in Pennsylvania when they got off Route 22. The rain had subsided and it was hot enough that steam was rising from the ground. I parked and caught up with the three people who had been my biggest supporters during my four years in college. For such a special day, a day of beginning and a day of ending, the talk at dinner was ambiguous. I think my parents were relieved that I had made it through college with a degree and in one piece. Sue was happy she wouldn’t have to type any more of my mundane history papers. The name of the restaurant was “The Old Homestead” and it was busy for a Sunday evening. I was unusually reflective as I devoured my steak and drank my suds. I was leaving a place that I had considered my home. I was leaving my friends and I was leaving behind four years at Muhlenberg that had shaped who I was going to be for the remainder of my life. I was going back to a world I use to know but had left behind both figuratively and literally. I did not have a job or a specific plan for the future. Yet on that night, I felt accomplished, I felt secure, and more importantly, I felt confident. Back in the car deep into New York, Supertramps’ song played again. “When you look through the years and see what you could have been…What you might have been.” Thanks to my years at Muhlenberg, for the first time in my life I was sure who I was.

The two cars were still in Pennsylvania when they got off Route 22. The rain had subsided and it was hot enough that steam was rising from the ground. I parked and caught up with the three people who had been my biggest supporters during my four years in college. For such a special day, a day of beginning and a day of ending, the talk at dinner was ambiguous. I think my parents were relieved that I had made it through college with a degree and in one piece. Sue was happy she wouldn’t have to type any more of my mundane history papers. The name of the restaurant was “The Old Homestead” and it was busy for a Sunday evening. I was unusually reflective as I devoured my steak and drank my suds. I was leaving a place that I had considered my home. I was leaving my friends and I was leaving behind four years at Muhlenberg that had shaped who I was going to be for the remainder of my life. I was going back to a world I use to know but had left behind both figuratively and literally. I did not have a job or a specific plan for the future. Yet on that night, I felt accomplished, I felt secure, and more importantly, I felt confident. Back in the car deep into New York, Supertramps’ song played again. “When you look through the years and see what you could have been…What you might have been.” Thanks to my years at Muhlenberg, for the first time in my life I was sure who I was.