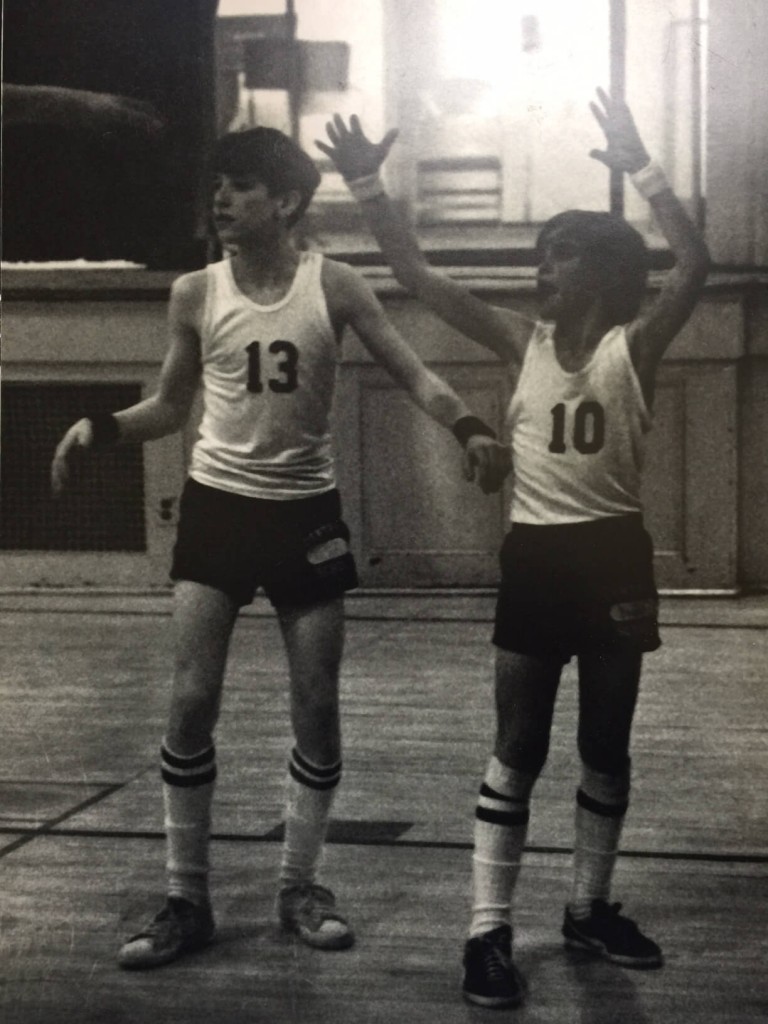

The big yellow school bus was pulling out of the New Paltz Middle School making its way through the early December gray. The kind of day Don Henley so aptly described with the lyrics, “The sky won’t snow and the sun won’t shine. It’s hard to tell the night time from the day.” It was just short of 1973 and I was a seventh grader on my way to my first school athletic event. I remember the large bus not being crowded and feeling a loud quiet surround me. I was heading into uncharted territory – the arena of competition. That adrenaline rush realm of keeping track of winning and losing was foreign to me. My good friend and teammate, Randy Freer, turned around from the seat in front of me, “How are you feeling Rich?”

The big yellow school bus was pulling out of the New Paltz Middle School making its way through the early December gray. The kind of day Don Henley so aptly described with the lyrics, “The sky won’t snow and the sun won’t shine. It’s hard to tell the night time from the day.” It was just short of 1973 and I was a seventh grader on my way to my first school athletic event. I remember the large bus not being crowded and feeling a loud quiet surround me. I was heading into uncharted territory – the arena of competition. That adrenaline rush realm of keeping track of winning and losing was foreign to me. My good friend and teammate, Randy Freer, turned around from the seat in front of me, “How are you feeling Rich?”

“I’m good,” I responded somewhat confused.

Then Randy said something that has stuck with me for 40 years, “If we are going to win today it will mostly likely be up to you.” It was the first time in my young life that I could feel the pressure that went along with the uncertainty of attempting to win. There were plenty of other people who cared about the game that day besides myself. I also realized that there would be times that others would be counting on me to get them into the winner’s circle.

From that moment, I understood that life on all levels was about winning and losing. That game of basketball amongst a bunch of 12 year olds played on a cafeteria floor in Marlboro, “NY” was some sort of microcosm to all of the games in life that were to follow. In a cosmic way, I was aware that today they were going to keep score and begin a sorting-out process of successful and unsuccessful middle school basketball players. Tomorrow on the loud speaker in homeroom, the results would be announced. Everyone in my tiny box of a world would know how much I played, how many points I had, and how I measured up against the players from another town. I did not, however, realize that this was just a precursor to keeping records of all things humans correlate with winning and losing. I was still innocent enough to not decipher that life was nothing more than a huge game. I couldn’t yet imagine that most people kept tallies in their heads. In many ways the wins and losses would be evaluated and judged by numbers: how many cavities did you have, class rank, SAT scores, girls or boys you kissed, letters after your name, credit score, dollars in the bank, salary, friends, trophies, square footage of your house, etc. The contest I was traveling to was the precipice of literally keeping track of victories and defeats and all the highs and lows that go along with those two outcomes.

My lips were now pressing against the cold bus window. I wiped my hand into the glass to move away the condensation. My eyes fixated on the cars going the other way. The passengers in those vehicles had no idea, nor cared, that one boy’s overly-reflective mind had just begun spinning into a whirlwind of anxiety. A tornado, that for all practical purposes, still has not settled. The people in my universe were going to take an interest in the results of today’s event. On some level, my team, my coach, and I would be held accountable today. Were we good enough? Had we prepared hard enough? Would we be able to execute what we had practiced? It wasn’t beyond me to comprehend that both sides would do everything they could to come out on top. At the time, it was the most important thing in our lives. The start of a lifetime learning process was going to take place inside the lines of that makeshift basketball court.

My lips were now pressing against the cold bus window. I wiped my hand into the glass to move away the condensation. My eyes fixated on the cars going the other way. The passengers in those vehicles had no idea, nor cared, that one boy’s overly-reflective mind had just begun spinning into a whirlwind of anxiety. A tornado, that for all practical purposes, still has not settled. The people in my universe were going to take an interest in the results of today’s event. On some level, my team, my coach, and I would be held accountable today. Were we good enough? Had we prepared hard enough? Would we be able to execute what we had practiced? It wasn’t beyond me to comprehend that both sides would do everything they could to come out on top. At the time, it was the most important thing in our lives. The start of a lifetime learning process was going to take place inside the lines of that makeshift basketball court.

Coach Karsten waved me off the warm-up line to have a private pre-game chat. I glided over across the shiny floor in my sleek blue suede Puma “Clydes” to get some last minute instructions from my mentor. “Rich, play like you have been in practice. Remember to relax and have fun.” Truth was, I didn’t feel nervous and was wondering why I was getting this kind of individual attention. I glanced around the exterior of the court and saw that parents from both sides were in attendance. My little league coach, Tom Roach, whose son Brian was on the team, was there. I saw Mrs. Freer (Randy’s mom) and I spotted Mr. Taylor, my backcourt mate’s father. What would turn out to be an aberration to the support I had always gotten, and would continue to get, I distinctly remember neither one of my parents being present. A boy younger than I sat at the scorers’ table ready to count the number of baskets and how many fouls each player committed. It was obvious that this competition meant much more than just having some fun. Once the game was underway, I was totally engulfed in the energy and electricity in the gymnasium. I could have been Walt Frazier running up and down the court at Madison Square Garden. It was a very tight game and as it approached the end, I felt as if the Marlboro Middle School was the only place on the planet.

Coach Karsten waved me off the warm-up line to have a private pre-game chat. I glided over across the shiny floor in my sleek blue suede Puma “Clydes” to get some last minute instructions from my mentor. “Rich, play like you have been in practice. Remember to relax and have fun.” Truth was, I didn’t feel nervous and was wondering why I was getting this kind of individual attention. I glanced around the exterior of the court and saw that parents from both sides were in attendance. My little league coach, Tom Roach, whose son Brian was on the team, was there. I saw Mrs. Freer (Randy’s mom) and I spotted Mr. Taylor, my backcourt mate’s father. What would turn out to be an aberration to the support I had always gotten, and would continue to get, I distinctly remember neither one of my parents being present. A boy younger than I sat at the scorers’ table ready to count the number of baskets and how many fouls each player committed. It was obvious that this competition meant much more than just having some fun. Once the game was underway, I was totally engulfed in the energy and electricity in the gymnasium. I could have been Walt Frazier running up and down the court at Madison Square Garden. It was a very tight game and as it approached the end, I felt as if the Marlboro Middle School was the only place on the planet.

The boys’ bathroom, posing as a locker room, had emptied out with the exception of one lone figure. The game had ended about a half hour ago and the bus was warmed and revving its’ engine in the parking lot. “Son that was some game you played today. I never saw anybody so small score all those points, 37, I think. Was this your first game of the season?” the stranger carrying a dust mop asked. The boy only nodded affirmatively, picked up his gym bag and moved past the man in uniform. “Hold up,” the man said firmly. “One more thing, I’m sure you’ll never forget this day. You found out how sweet it feels to win, to be the hero. Enjoy it, treasure it, but keep in mind you don’t really learn anything until you’ve lost. You can never fully appreciate conquest until you get knocked down.” By now I was standing still as a school janitor imparted his unsolicited words of wisdom.

The boys’ bathroom, posing as a locker room, had emptied out with the exception of one lone figure. The game had ended about a half hour ago and the bus was warmed and revving its’ engine in the parking lot. “Son that was some game you played today. I never saw anybody so small score all those points, 37, I think. Was this your first game of the season?” the stranger carrying a dust mop asked. The boy only nodded affirmatively, picked up his gym bag and moved past the man in uniform. “Hold up,” the man said firmly. “One more thing, I’m sure you’ll never forget this day. You found out how sweet it feels to win, to be the hero. Enjoy it, treasure it, but keep in mind you don’t really learn anything until you’ve lost. You can never fully appreciate conquest until you get knocked down.” By now I was standing still as a school janitor imparted his unsolicited words of wisdom.

From the other end of the corridor I recall hearing another voice shouting for me, “Siegel, let’s go everyone’s waiting!” Without ever uttering a word, I turned and headed through the exit into the cold December night air.

From the other end of the corridor I recall hearing another voice shouting for me, “Siegel, let’s go everyone’s waiting!” Without ever uttering a word, I turned and headed through the exit into the cold December night air.

The oddly placed soliloquy was still ringing in my ear as I made my way up the steps toward my ride home. In unison, my teammates, scorekeepers, and Coach Karsten stood up and gave me a big round of applause. For an immature 12 year old, the adulation and acceptance felt misplaced and embarrassing. It was the first official game I had ever participated in and basketball was, after all, the ultimate team game. I was conscious that no one player should be singled out so profusely in a game built around teamwork. I sheepishly made my way through slaps on the back and high fives all the way to the back seat of the bus. Basking briefly in admiration and stardom, I tried to find some sense in the words of the mystical custodian. In all the time between that day and now, it turned out I’ve had many occasion to stomach the lessons of losing. In love, business, and on the athletic fields, I have felt more than my share of the inadequacy that goes along with not achieving a desired outcome. That may be why I repressed many of my early accomplishments and triumphant moments until all these years later. Looking back, I don’t think I deserved, or was ready to fully appreciate, the kind of glory I encountered that day in Marlboro. It’s only after all the decades of being knocked around and struggling to find my way back up that I can finally embrace the applause.

Looking back, I don’t think I deserved, or was ready to fully appreciate, the kind of glory I encountered that day in Marlboro. It’s only after all the decades of being knocked around and struggling to find my way back up that I can finally embrace the applause.