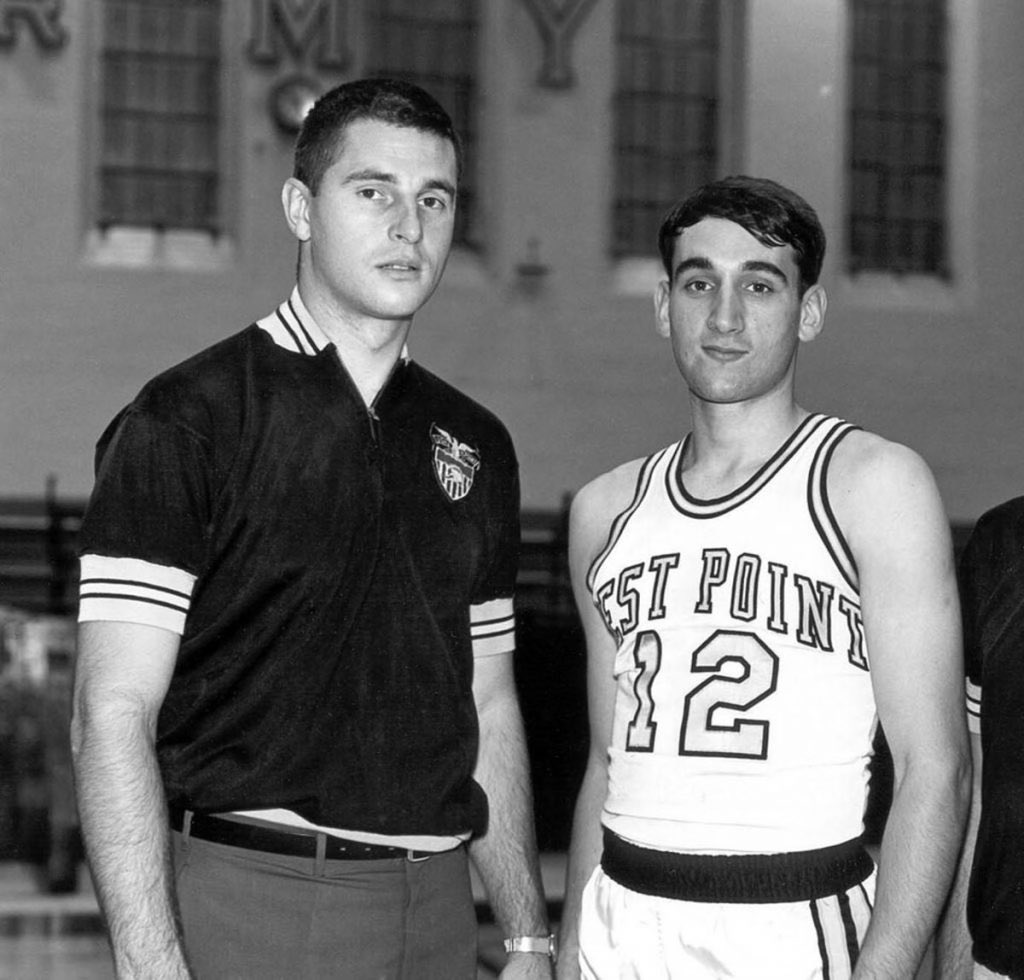

The wind was whipping hard off the banks of the Hudson River. It was a bitterly cold January night on the grounds where America’s Generals are manufactured. I was eight years old making my first visit to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Myself, my dad, and my brother were getting ready to enter the venerable Army Gillis Field House, home to the 1968/1969 Cadet basketball team who had the nation’s basketball community buzzing about the young gun the Army had hired to run their basketball program . As my family found refuge inside the warmer, but still frigid field house, my dad leaned over and spoke to me in a reverent tone, “Richie, keep a close eye on the coach of Army.” It’s hard to forget the way my father said those words to me. I remember thinking ‘wow this guy must be special, because my dad was not easily impressed.’ As if he was delivered from the night sky, from the top steps of the arena, strode a determined looking young man who had been the West Point Men’s Varsity Basketball Coach the prior three seasons. Robert Montgomery Knight was 30 years old and had already been anointed by the New York City sports media with the nickname of “The General.” That cold night heated a passion for basketball in me that would last for 20 years. In the next two decades all thing B-ball would be a top priority in my life. My mentor in that span of time was Bobby Knight.

On that night, from the moment I laid eyes on the fiery leader of the cadets, I decided I was going to play college basketball at whatever college he would be coaching. I quickly discovered that there was a consensus among sports writers, and Army hoop followers, that Bobby Knight, in his mid-twenties, had established himself as one of the top teachers in the country. It wasn’t just that his undermanned Cadet team (In those days if you were over six foot five you could not attend any of the three Military Academies) were beating some big-time programs. It was the way they played defense that got more attention than the victories. His team’s played with a sense of intensity and purpose of which I have yet to see matched. That January night, as I sat packed in warmly between my dad and brother, with 5,000 other witnesses, watching a passionately crazed baby-faced man stalk the sidelines like a tiger stalking his prey. Knight saw himself as Patton chasing Rommel through the dessert. That night I watched him berate officials, scream like a madman at his team, and mostly will his team to an 81-66 win past Seton Hall. Playing point guard that night was a kid from Chicago named Mike Krzyzewski. In one night, I saw the greatest coach of his time coaching a player who went on to break all his mentor’s coaching records. Long before Nolan Richardson’s Arkansas team of “40 minutes of hell” or Frank Davis’s “94 tight” Knight’s West Point teams picked up opponents’ base line to base line providing a clinic in suffocating man to man defense. What I felt that night in the Army Field House turned out to be very real. I went on to play four years of basketball in college and became a High School Varsity Basketball Coach at the age of 24.

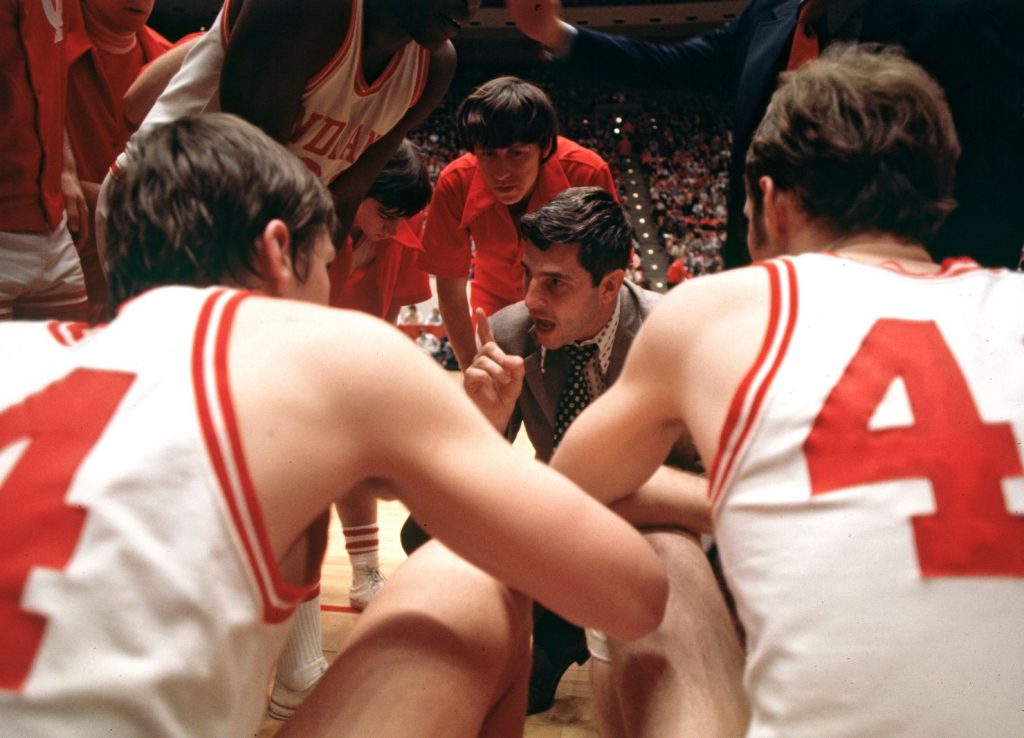

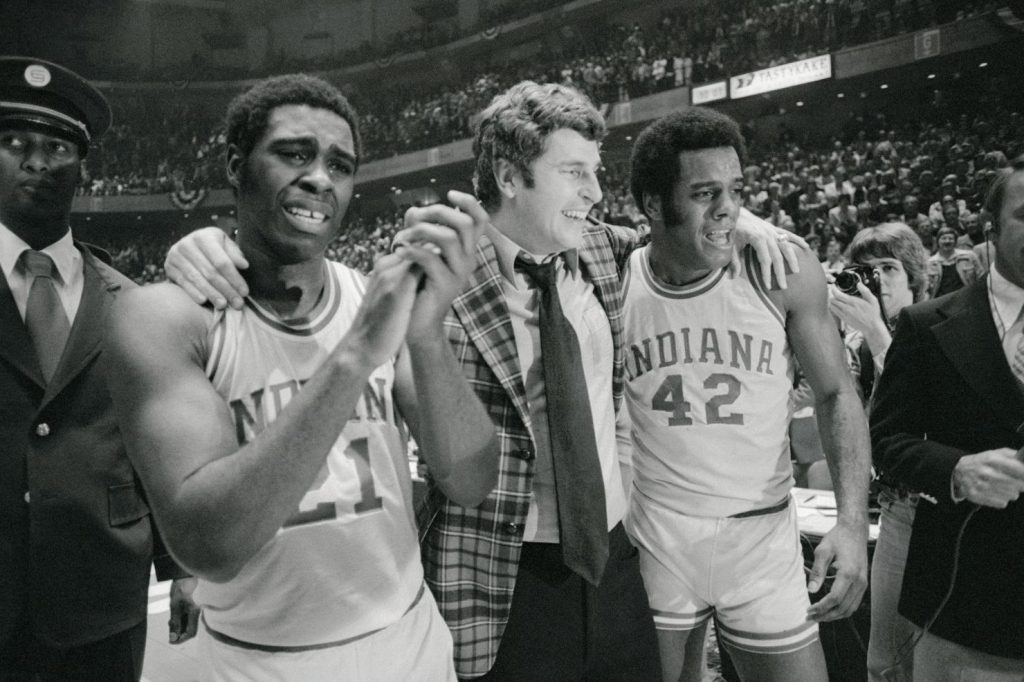

As I was beginning my coaching career Coach Knight had moved on to Indiana University. With the Hoosiers, Knight would win three National titles, including his undefeated 1976 team. They are still the last Division I College basketball program to go a full season without a loss. In the years I was playing and coaching basketball (1970-1990) Knight was easily the most recognizable name in basketball. Some loved him, most hated him, but 95% of those who played on his teams would take a grenade for the team, or their General. He coached the game in a time before there was anything known as “a player’s coach”. If you elected to play for “The General” you understood from day one it was “his way, or the highway”. His players played each possession as if it were their last. His players never, ever, questioned orders or strategies. The few times I saw anyone challenge Knight they were instantly refuted, embarrassed, and sometimes physically assaulted. Playing for Knight meant every practice and every game you were going to leave every ounce of effort you had in your body on the hardwood floor. The General’s teams respected all, feared none, and the players that made it through four years graduated 100% of the time. In my years playing college basketball I would always look back to those Bob Knight Army teams and focused on playing every night and every practice with that type of intensity. After graduating from college, I was ready to teach the kids about General Patton in the classroom and imitate Bobby Knight on the basketball sidelines.

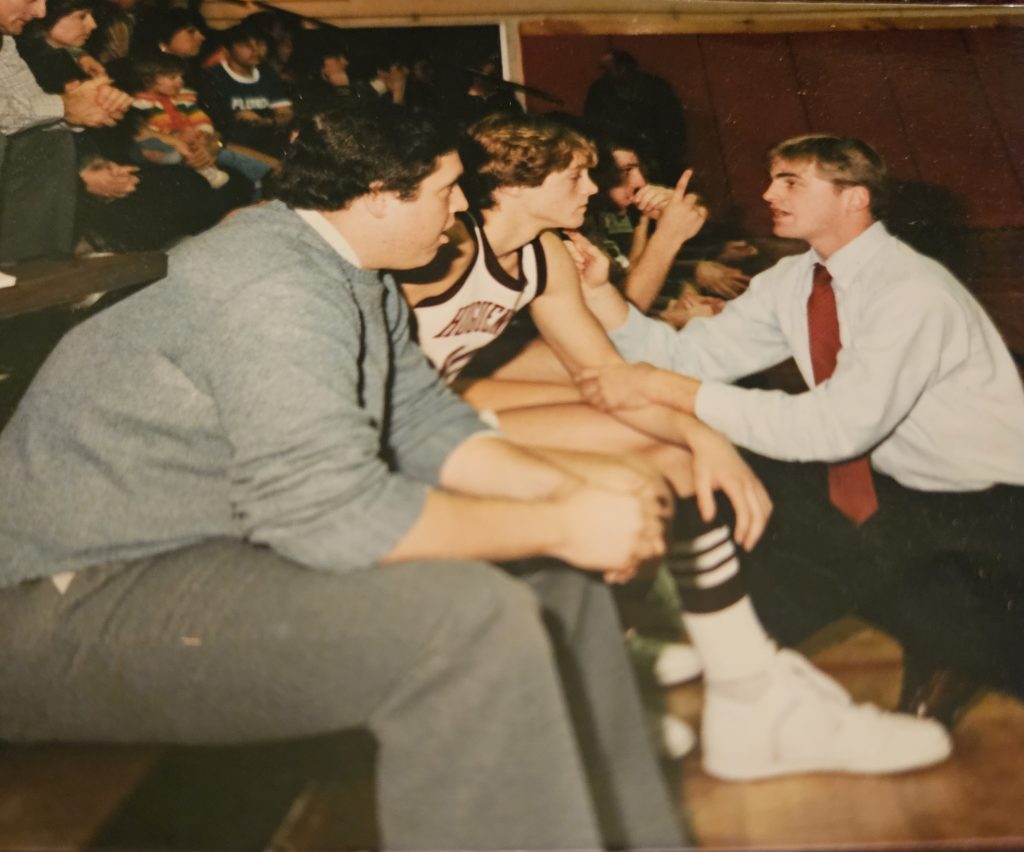

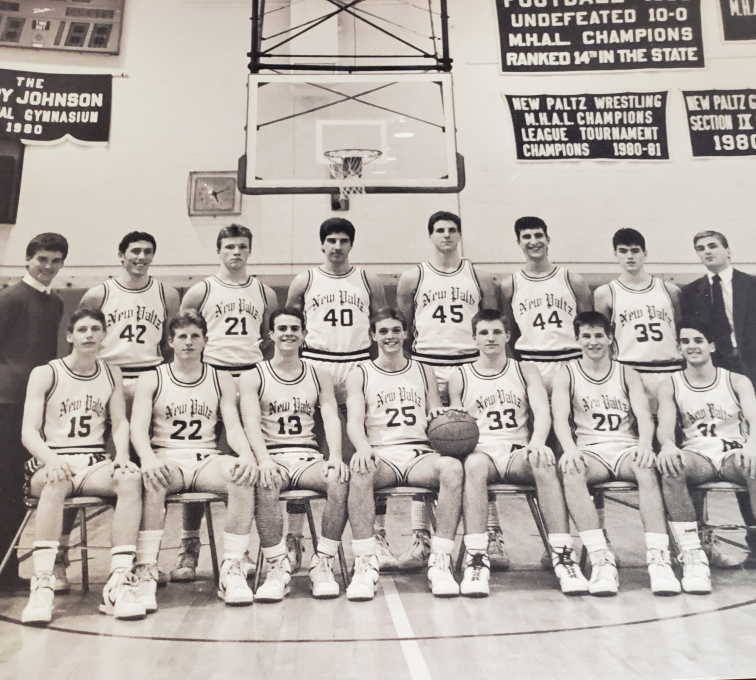

My coaching and teaching career began in Pine Bush, New York in 1982. My first gig was as the J.V. basketball coach for the “Bushmen” (literally their nickname) which was located 30 minutes due west of West Point. I was confident I was on a course to be one of the top coaches in the area. In everyday life I have no problem being “an original”, yet in my initial years of coaching it was obvious that I was doing too much mimicking. After three years of a very successful run with the “Bushmen” my alma mater came calling. John Ford was the athletic director at New Paltz High in 1985. “Rich we have been watching your progress the last few years. We are excited to offer you the position of varsity basketball coach. There is one thing I want to make clear before you accept, I will not tolerate any Bobby Knight type antics.” The year before, “Coach Knight”, on a warm February afternoon in Bloomington Indiana, got overheated and threw his chair across the floor of Assembly Hall as a Purdue Boilermaker stood on the free throw line preparing to shoot technical fouls. For his loyalists, the winning deflected his bullish behavior. The very next year (1986/87) Knight would go on to win his third and final National Championship. I lasted four years as the coach at New Paltz. The honeymoon was short and bittersweet. There were more than a few rewarding moments. The best one was meeting my wife Donna whose brother was on my team. At the time I was coaching , the game itself was going through some major changes in the rules. The three-pointer arrived, the transition game became a priority, and passing up a two-footer for a 25-foot jump shot became a strategy. It was not until the September, before what would have been my fifth season, that the athletic director called me into his office. I knew it was coming, “Rich, the school board of the New Paltz School District has decided they do not want ‘a win at all cost type coach.’ They have instructed me to not renew your contract for the upcoming season.

My dismissal turned out to be an abrupt ending to my official affiliation with basketball. There were other offers and opportunities, but the days of being the next Bob Knight were finished for myself. While I was making the first big transition of my adult life Coach Knight was digging a hole for himself in Indiana. The age of videotape would provide the concrete proof of the type of abuse he dished out to all who had direct contact with him. Besides throwing a chair on the court during a game, he poked officials and players in the chest, and he verbally accosted Indiana University’s administration in the press. Finally, after violating a “zero tolerance” order, despite three National titles, 902 wins, and a legacy of being one of the best to ever to roam the sidelines he was given his walking papers by Indiana President Myles Brand in 2000. A year later the now neutered General accepted the head coaching position at Texas Tech. From 2001-08 Knight did well enough not to tatter his reputation as one of college basketball’s most impactful mentors, before retiring and moving into the television analyst booth. Although his continued boorish behavior caused him to lose some of the luster for me, I choose to remember the “Army Bob”. Bobby Knight was a very well read and intelligent man. In another time Knight would have been a top General in the United States Army, commanding troops in places like Normandy or the Philippines. Not unlike many old General’s, coach Knight could not find a way to evolve. He went into the millennium hanging on to his stubborn mantra of “my way, or the highway”. In the end, the man who once commanded the audiences of Presidents turned into a sort of caricature of himself.

The news came down last week, Robert Montgomery Knight had passed away at the age of 83 due to complications related to Alzheimer’s. It has been 54 years since that childhood “Knight” that I was introduced to an imposing figure, fittingly wearing a G.I. Joe haircut. My eyes fixated on a college basketball coach nervously pacing back and forth. He was like a bobcat, growling, staring, constantly screaming instructions to his team, and with his mere presence intimidating the opponent. Like the infamous 17-year-old bank robber, “Billy the Kid” his legend grew rapidly far and wide. The 6’5” former Ohio State sixth man took very little time to establish himself as the quickest draw in college caging. By the time Knight became head coach of the Hoosiers, he had established himself as a hoops guru, particularly on the defensive side of the ball. Every High School basketball coach in America signed up to attend instructional clinics conducted by Bobby Knight. When he spoke basketball everyone within hearing distance came to attention. When an order was shouted to one of his players, they carried it out exactly, or their ass went to the bench.

Bobby Knight lived in a space inside his mind where winning was not optional, losing was unacceptable. The record shows Knight won consistently (902-371), and he won within the rules of the NCAA. To me his most impressive credential is that 100% of the players who played four years for him walked across the stage at graduation. I still hear myself screaming “See the Ball” as I encourage my charges on defense. Until I sat down to write this story, I had not realized that I was merely channeling the voice echoing from West Point’s Gillis Field House all those years ago.